Falcon 9’s History Explained - SpaceX’s Upgrades that Led to Block 5

The End of Falcon 9 History?

After nearly a decade of development, SpaceX will soon debut the final design of its Falcon 9 rocket. SpaceX’s primary launch vehicle has advanced a long way from its early beginnings, but now its continual improvement will stop for the foreseeable future. In order to be human-rated for NASA crew flights, a rocket must have at least seven launches using the same design. SpaceX can no longer pencil-in changes with every launch. Now it has to finalize a blueprint. That design is the so-called “Falcon 9 v1.2 Block 5.”

The upcoming Bangabandhu-1 launch debuting Block 5 has electrified SpaceX fans but has also clouded the details surrounding Falcon 9’s development history. This post is intended to clear the skies by aggregating the publicly-available details of previous rocket versions. I wasn’t satisfied by general reports of “uprated thrust” and “redesigned engines,” so I set out to find the specific changes that evolved a Dragon-launching Falcon 9 v1.0 into the rapidly reusable Falcon 9 v1.2 Block 5.

V1.0 Block 1

A Falcon 9 v1.0 Block 1 launching a Dragon capsule. (Photo by By Tony Gray and Robert Murray)

Falcon 9’s story starts with version v1.0 Block 1. It only flew five times - three demonstration launches to meet NASA requirements, and two Dragon launches to the ISS. Yet even at this early stage, SpaceX was eyeing reusability. V1.0 tested out a recovery system intended to gently splashdown the first stage in the ocean using parachutes. However, the plan failed when the boosters and accompanying parachutes were destroyed on reentry. The waiting recovery boats only ever recovered pieces of the first stage [1].

V1.0 Block 2 (Never Built)

Before v1.1 was designed, SpaceX planned to extend v1.0’s length to 180ft (55m) but still rely on Merlin 1C engines. This version of Falcon 9 never flew after SpaceX pivoted to v1.1, an even larger and more improved rocket.

V1.1

After meeting NASA requirements using v1.0, SpaceX went back and upgraded the design to v1.1 - increasing payload lift capacity by 80% and marching ever closer to full reusability [2].

Upgrades:

-

First attempt of propulsive landing - Three-engine entry burn followed by a single-engine landing burn [2][4]

-

Simplified connection between first and second stages - Nine hardware interfaces and three pusher elements that ensure stage separation were replaced with three connectors with integrated pushers. Musk said, “We go from 12 things that can go wrong to three at the point of staging.” [2]

-

Increased in-house production [7]

-

Grid fins added to control booster reentry and descent - Debuted both open-loop and closed-loop hydraulic systems (estimated date for closed-loop adoption). [8]

Unpainted aluminum grid fins. (Photo by SpaceX)

-

Upgraded avionics - Introduced triple-redundant flight computers and created new software based on Dragon’s flight-proven unit. - “You could put a bullet hole in any one of the avionics boxes and it would just keep flying,” Musk said. [2][9]

-

Stronger heat shield at the base to survive re-entry [2]

-

Merlin improvements in reliability - high-efficiency processes, increased robotic construction and reduced parts count [2]

-

M1D thrust to 140,000lbf from 95,000lbf [10]

-

Introduced 70% throttle capability on the first stage - Instead of staging engine shutdown prior to stage separation, the rocket could now simply throttle all engines to limit its acceleration. [10]

-

Removed structure from Merlin 1D engine to reduce weight - Each engine now weighed less than 1,000 lb (excluding thrust-vector-control system).[2][10]

-

Upgraded the Merlin propellant injection system - Replaced two fuel and oxidizer valves with a single unit [2]

-

Increased Merlin chamber and nozzle thermal margins [10]

-

Ablative engine bumpers to prevent mishaps during gimballing [2]

-

Improved manufacturing of the chamber jacket - Elon explains this best: “The hardest part of the engine to mass produce is the electroplating of nickel-cobalttothe chamber. We create this thick metal jacket that takes the primary stress of the pressure vessel and it’s plated one molecule at a time. Plating is about the slowest way you can make a metal thing. With the Merlin-1D we take a metal jacket that is explosively formed. We take a metal sheet that’s in a cylindrical form and put it in a bucket of water, effectively. Sort of a concrete pool. And you set off an explosive and the jacket just goes “boohmp” and forms to the outer side walls into a jacket shape, so you have a mold, effectively. And then you just put the jacket on the chamber and braise it on. You can do several a day.” [11]

A Merlin engine during operation. (Photo by SpaceX)

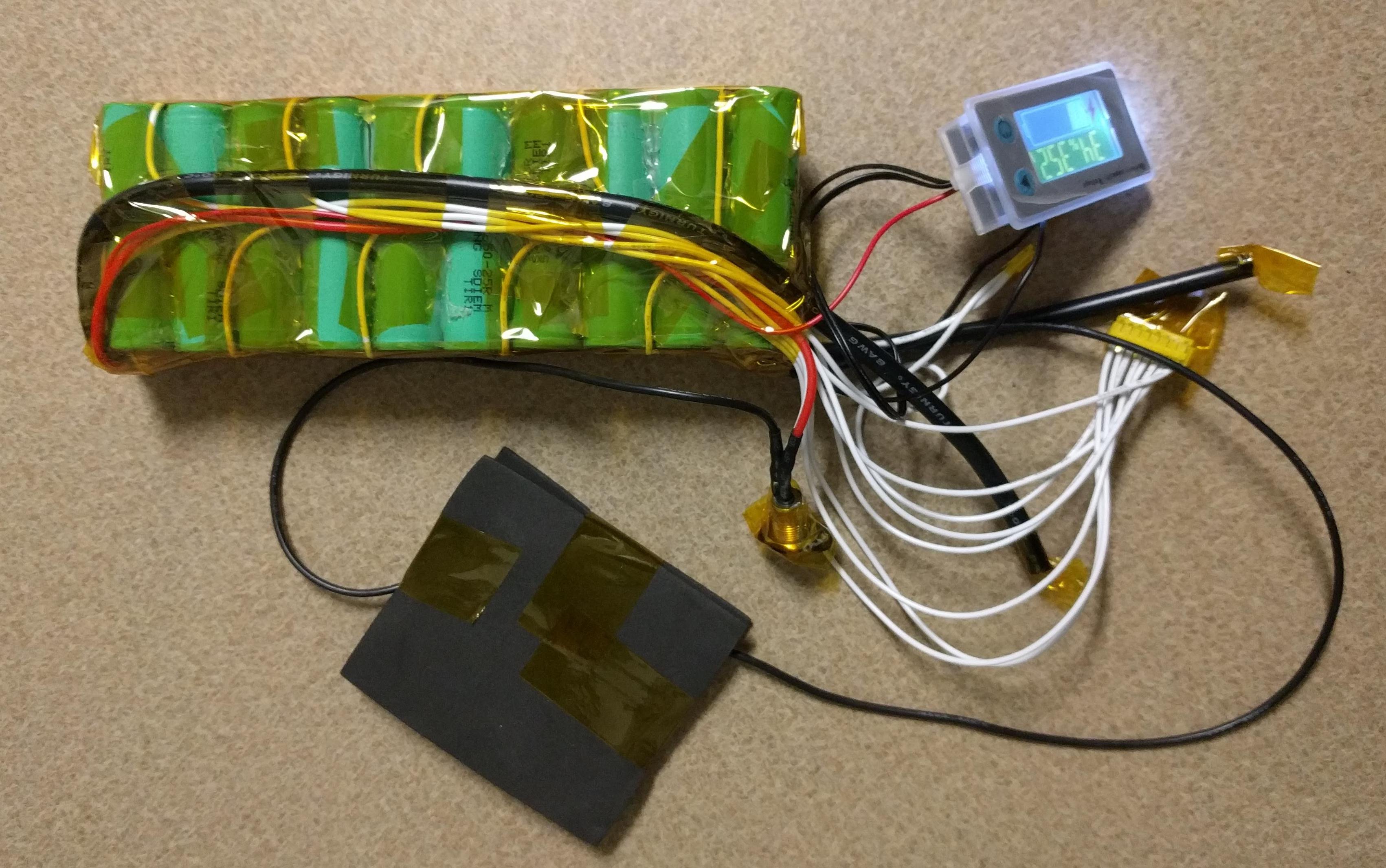

V1.2 Blocks 1-3

With v1.1 SpaceX got close to recapturing a first stage, but with the next design iteration, SpaceX would finally accomplish what many thought was impossible: recapturing an orbital class first stage booster. The upgrades included increases in engine performance and structural changes aiding reusability. Even though these boosters could theoretically be reused 2-3 times, SpaceX has never launched this design more than twice. [16][23]

Upgrades:

- 33% performance increase - Allowed for drone ship landings on missions to geostationary transfer orbits [14] [15]

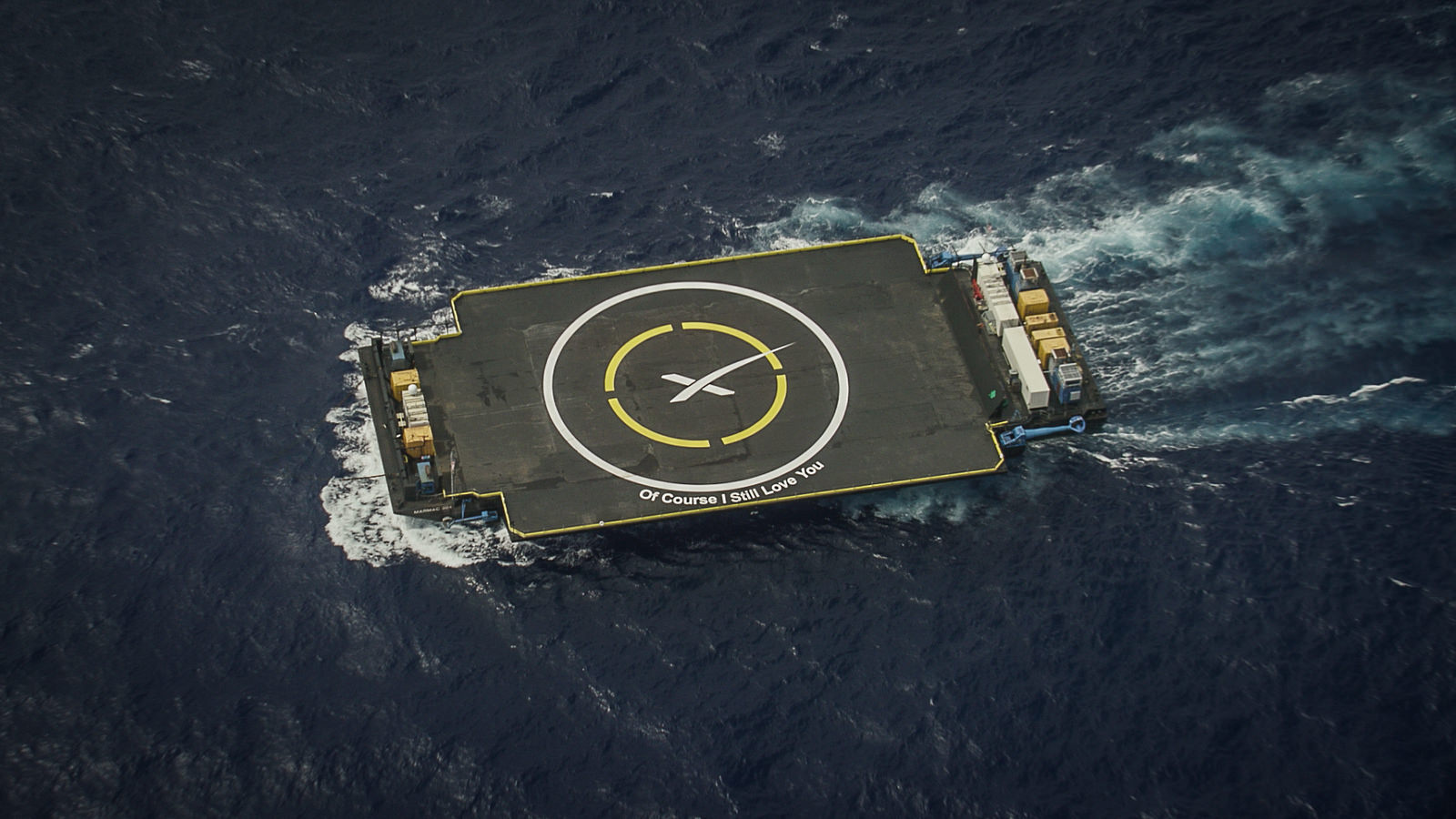

Of Course I Still Love You - The original autonomous spaceport drone ship stationed off the eastern US coast. (By SpaceX via Flickr)

-

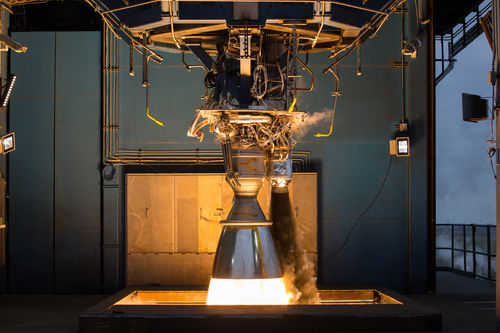

Increased engine thrust - In June 2017, Gwynne stated they tested the Merlin engines up to almost 240,000lbf - “In order to launch and get operational with …v1.1, we needed to draw a line on engine development. But what we did see during the development of our Merlin engines … was that there was more performance to go get, …so…we’ve gone back, got that extra performance from those engines.” [14][16][17]

-

Deeper cryogenic cooling - LOX densification from 70lbs/ft^3 to 75lbs/ft^3 by chilling to -297 degrees F. 7% increase in density [12][18]

-

Deepened Merlin lower throttle range to 40% [19]

-

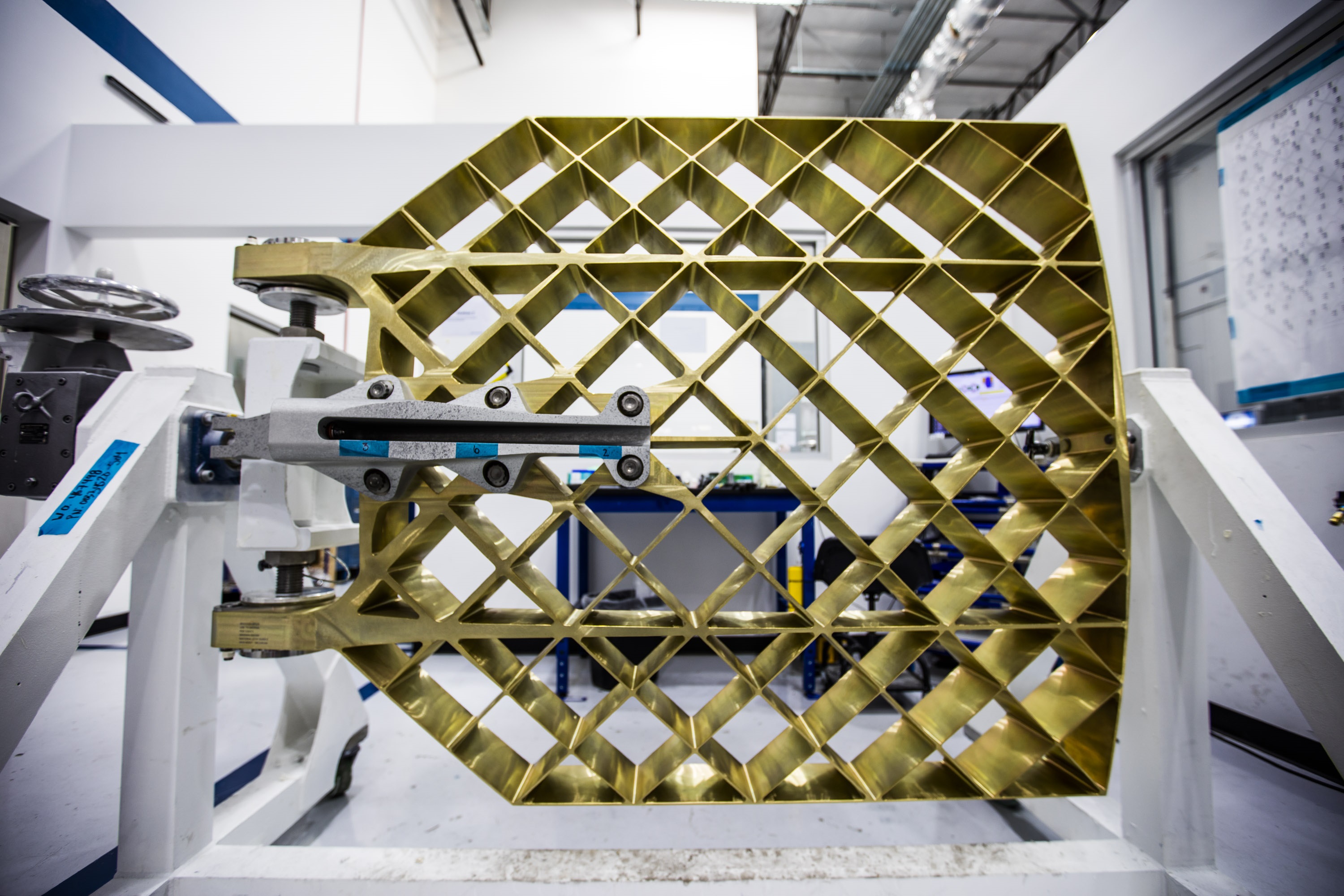

Upgraded grid fins - Switched from painted aluminum to unpainted, single cast titanium. The heavier grid fins “should be capable of an indefinite number of flights with no service.” [20][21]

Updated grid fins as debuted on the Iridium-2 mission. (By SpaceX via Twitter)

-

Longer interstage [21]

-

Modification of structure to streamline production - Gwynne quoted as wanting to only manufacture two core types: one for FH center core and one for the side boosters/single stick F9 [14]

-

Modified octaweb configuration [21]

-

Upgraded first stage landing legs [21]

-

Second stage Merlin thrust increase [21]

-

Second-stage nozzle lengthened [21]

-

Second stage propellant storage increased [18]

-

Minor electronic improvements [18]

-

Debuted Fairing 2.0 - Slightly enlarged the fairing and added hardware aimed at making the fairing recoverable. After protecting the Paz satellite during flight, one of the upgraded fairing halves was guided to a recovery ship using onboard thrusters and a parafoil. The fairing half missed the ship’s waiting “catcher’s mitt” by a few hundred meters but landed intact. [22]

A fairing 2.0 half floating in the ocean after a missed capture. (Photo by SpaceX)

V1.2 Block 4

Not many specific details exist regarding the next design iteration of Falcon 9. The only concrete fact I could find was upgraded engines[24]. According to Gwynne, Block 4 mainly serves as an incremental transition between Block 3 and Block 5 [16]. Differentiating these three blocks is further blurred by SpaceX’s design change implementation. SpaceX got better at smoothly introducing changes to Falcon over time. With less effect on manufacturing, design changes were continuously implemented rather than introduced in disruptive batches [16].

What is interesting to note about this design change is its debut. Before complete Block 4 Falcon 9’s were launched, Block 4 second stages were fixed to the previous design’s first stage. This scenario involving Franken-Falcons only occurred three times: NROL-76, Inmarsat 5, and Intelsat 35e. This information led many to believe Block 4 changes involved military launch requirements and increased second stage performance.

A reused first stage launching a previously-flow Dragon capsule for the CRS-14 mission. (Photo by SpaceX)

V1.2 Block 5

Finally, we’ve reached the end…or at least the start of a temporary design freeze. Block 5 is built to meet NASA crew requirements while at the same time demonstrating rapid and dependable rocket reusability. Any SpaceX rocket must meet high demands, but now Gwynne Shotwell has expressed SpaceX’s desire to launch more reused rockets than new builds. That feat just years ago was only imagined in science fiction. Now it’s a tangible reality. Block 5 is built to fulfill that long-held aerospace wish. And because the design must remain unchanged for at least seven flights to attain crew rating, the launcher will also serve the majority of SpaceX’s clients for the foreseeable future. That means working through a manifest worth $12 billion dollars. To meet these goals and to lower the cost barrier to space, Block 5 comes with plenty of updates.

Upgrades:

-

Black interstage, landing legs, and raceway [24]

-

Retractable landing legs [24]

-

Redesigned COPVs - Both to account for Amos-6 disaster and to handle many reuses [16][24]

-

Redesigned turbopumps. - NASA required SpaceX to redesign its Merlin turbopumps for crew rating after recaptured units showed stress cracks in the turbopump blades [24]

-

Other general Merlin engine improvements - Thrust increased to 190,000lbf [16]

-

Redesign and requalification of active components - Valves for “longer duration and higher levels” [16]

-

Redesign of octaweb thrust structure - Bolted rather than welded [16]

-

Optimized for reusability - Can refly a dozen or so times with inspections and up to 100 flights with refurbishments. [16] “Aiming for two flights within 24 hours”

Recaptured first stages in a SpaceX hangar. (Photo by SpaceX)

Side Note - Merlin Engine Takeaway

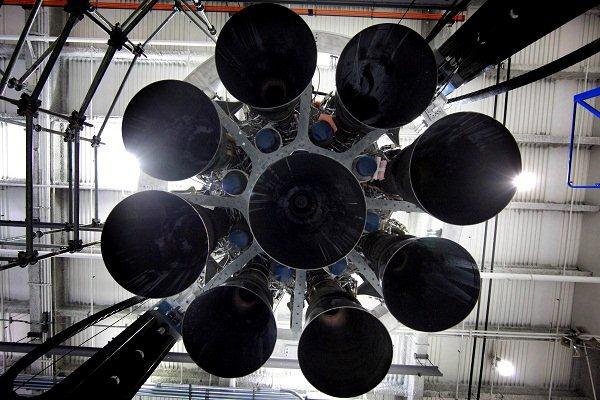

Throughout Falcon 9’s development, the rocket’s Merlin engines repeatedly increased their performance. With every iteration, there was an accompanying higher thrust rating. I actually decided to not include thrust numbers with each F9 version because the upgrades were so frequent - even within block versions.

The original Merlin engine only had 60,000lbf (and was rightly named ‘60K’), but now we’ve heard public thrust numbers of up to 240,000lbf. That 4X thrust increase is even accomplished with a lighter engine design. Now the name change to ‘Merlin’ (a species of falcon) makes sense. A ‘Falcon’ grows larger while ‘60K’ just grows more outdated.

Using a rough estimate of 1000lb engine weight and the highest reported thrust of 240,000lbf, the T/W ratio comes to an astounding 240! Although not the best metric for engine performance, the incredible thrust-to-weight ratio of the Merlin engine is indicative of impressive engineering.

Summary

Falcon 9’s history is clearly long and winding. The initial v1.0 rocket underwent a few growth spurts, some wardrobe changes, and countless internal tweaks to become the adult Block 5. Because of this, the growing rocket continually questioned its identity. At various times in its life, it’s been called Falcon 9 v1.0, Falcon 9 Block 2, Falcon 9 v1.1, Falcon 9 Upgrade, Falcon 9 v1.2, Falcon 9 Block 3, Falcon 9 v1.1 Full Thrust, Enhanced Falcon 9, Full-Performance Falcon 9, Falcon 9 Block 4, Falcon 9 v1.2 Block 4, Falcon 9 New Design Spin, Falcon 9 Block 5, Falcon 9 v1.2 Block 5, and Falcon 9 Version 7.

Don’t let the names confuse you. The major iteration changes are easy to understand if you think in terms of utility (or at least what outsiders perceive as utility). I’ll stick to the four most widely publicized iterations: v1.0, v1.1, v1.2 Blocks 1-4, and v1.2 Block 5.

The first Falcon 9 design fulfilled NASA requirements to launch cargo to the ISS. That was v1.0. Once those requirements were met, SpaceX felt comfortable going back, testing new design features, and increasing performance for reusability and private customers. That was v1.1. Then with each landing attempt, SpaceX honed its blueprint. Those frequent lessons, along with military requirements and a desire to recapture GTO boosters, fostered more upgrades. Smooth implementation made this development continuous and ill-defined. That was v1.2 Blocks 1-4. Then Commercial Crew requirements eventually ended the party when its inevitable design freeze marched too close for comfort. The final update appeased engineers by including safety changes, reusability optimizations, and ultimate performance increases. SpaceX’s rocket finally matured and is now ready for humans. That is v1.2 Block 5.

Note: This story was originally posted on my old blog (theclimategap.com) but was edited slightly and moved here in 2022.